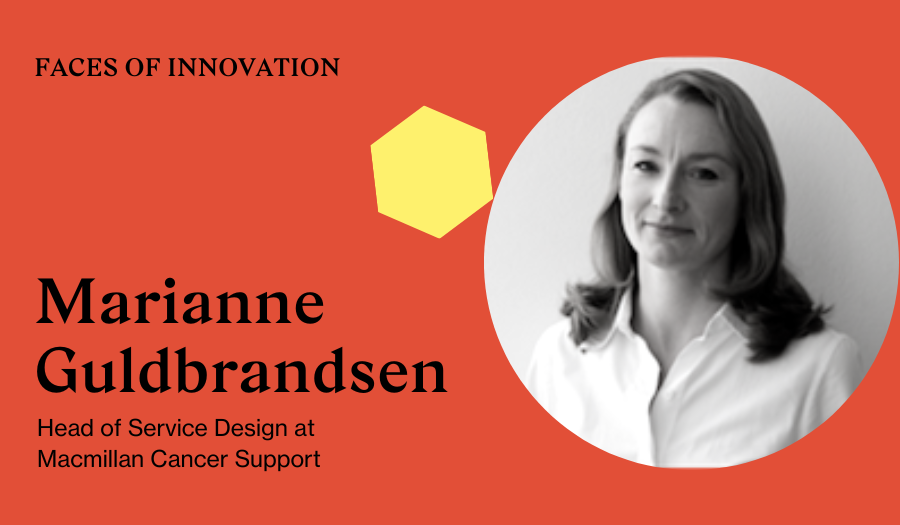

She speaks about the challenges of building service design thinking into large organisations, her ‘firm but flexible’ approach to her work, and how she has embedded the way of thinking into her team. We also touched on AI and what she does to provide fresh inspiration for her team of innovators.

Could you begin by introducing yourself and talking about your role at Macmillan?

Yes, I can definitely do that. I have been at Macmillan for nearly four years. It’s quite an interesting story, actually, becauseI had been at the Design Council for a number of years and then also worked as an independent innovation service design consultant for a few years. I was actually freelancing at the time when I got contacted by Macmillan.

They said, “Are you interested in heading up a team?” They didn’t call it service design. I think they called it innovation and strategic partnerships. They’d been looking for a year. The challenge had been that first they hadn’t really put it out as an innovation role, it was more senior strategic partnerships to partner with the NHS and other organisations and come up with new service solutions.

How did you know it was a service design role?

Purely because I think they had asked other design agencies if they knew anybody good and they pointed to me. It was through word of mouth and what they’d seen other agencies do. What’s interesting is Macmillan didn’t really have the language around service design. I think that’s probably quite an interesting point because you’ll probably still see that even now, four years down the line. It gets mixed up with UX design. There are lots of nuances that I don’t think are necessarily well understood in the market.

I think we have an obligation to help educate our clients. Understanding what makes good user experience, from understanding unmet needs or needs that are not necessarily expressed. I think often we get a little bit too hooked on what is a need and sometimes it’s a desire and sometimes it’s not even identified. It’s more nuanced. I talked very much about that when I was interviewed. I talked about the innovation process and how that was important for me.

That sold me basically because there was a need for bringing both a user focus but also a process into an organisation that’s done innovation very well for many, many years but had also grown exponentially over the last seven, eight, nine years, which meant the organisation was now getting so big that there was a need to standardise some of these processes and thinking about how can we be more efficient and effective when we come up with new ideas. That was basically the role.

A wonderful thing in Macmillan is that we have a lot of pilots here. Lots of things get started, lots of good ideas.

What methodologies did you need to introduce and up-skill people in?

You could say the biggest thing has been to give the organisation a design process or, as some would call it, an innovation process. I’ve basically tailored the double diamond design process or innovation process.

Originally it didn’t really include implementation and I have included this in it. It doesn’t necessarily distinguish piloting, prototyping, which is something I have put very clearly in it.

We’ve given the organisation an innovation process based on the double diamond but it’s also now very much tailored to Macmillan. I would say it’s a combination of a traditional flowing design process but because it’s such a big organisation, it’s also the whole layering of what you would normally find in engineering, which is a stage gate model. You have gates you go through and you have sign off points. The idea is that you link funding to some of those gates.

I think in some ways you could say it’s about how do we keep something firm and flexible at the same time? It’s a really, really fine balance. It’s something I talk to my team a lot about, how can we be firm but flexible? You need a process that everybody can understand but you also need some design points that are, in some ways, non-negotiable because otherwise you can do something, go through a gate, realise that maybe you didn’t do enough at the first stage, start doing something.

The gates are quality gates basically. I think one of the things in general that’s difficult for non-designers - and maybe even for designers sometimes - is when have you defined your problem well enough.

How do you go around gathering support from the c-suite and how often do you have to build those conversations into your day to day work?

You could say I have been extremely lucky that there was buy-in from the CEO at the beginning of building my team. There is an understanding high up that there is a need for people

that understand innovation and service design.

Macmillan has always understood the word ‘innovation’. At the top it was very well understood as something new, though I don’t think it was necessarily understood as something you can put through an organised process. There was a thought about a good idea, let’s go and do it and, very often, let’s be radical. What’s the next Google watch for Macmillan? Whereas I would come in and say, “Okay, that’s fine but how many people are going to be able to afford Google watch for Macmillan anyway?”

Also, I came in very much with a sense of, ‘let’s make sure we understand the full breadth of our audience’ and also, ‘let’s tackle the hard to reach or other things’. The point being, I had buy-in. I would definitely say I’ve been extremely lucky that not only have I had buy-in from senior leaders, I think I’ve also been able, my team has been able to navigate that space between being firm around what does good design process look like and also be flexible, how do you do it in a charity?

Firm but flexible. I suppose you carry this forward for the external partners you outsource work too?

I only want to outsource in areas where we don’t have the capacity to do something.

What areas would those be? I guess more of the initial insight?

Yes, so design ethnography for instance. And user research. It could be to come in and do some rapid prototyping and start doing some coding or it could be all sorts of things. I think it’s been really important for me to send the message across to the organisation that we are a small multidisciplinary team and I’ve only really so far outsourced because we didn’t have the capacity in the team.

I just had a very strong belief that if you want to embed a design methodology and a design culture, there’s a limit to how much you can outsource because a lot of it is about actually landing things. Not just landing good reports that you can outsource but actually embedding that mindset. We would work very closely with internal teams. I think for me, the big distinction between what you should outsource and not outsource is you can outsource if you don’t have the capacity.

So you would get more support for a function that’s already there?

I don’t think it’s about support because people are very happy to outsource.I think if you really want to learn this methodology and you really want to embed it in the organisational culture

You can’t just let someone else just do it.

You will end up with lots of different ways of doing it. More importantly, you will not get implementation necessarily.

It’s probably where you could say that Macmillan is an organisation that’s a little bit different from commercial businesses because in commercial businesses it’s about customers buying your product. Then you can look at the revenue and stuff like that. Whereas for us, it’s actually more about the end user experience and us being able to identify that it’s not completely random that because they had this experience they’re feeling better. Being able to prove impact has become more and more important.

I always like to ask people who work in innovation how innovative they are internally as well. What kind of stuff do you guys do to make sure that the culture within your team is fresh and interesting?

I think some of this is also about having a team that is collaborative and able to reflect on lots of different things. Where we try to keep fresh in terms of what does innovation mean is that we run a number of sessions where we invite people in to come and talk about what they’re doing.

I think it’s very important to look outside of the organisation to stay fresh. Then the other thing we do is every six weeks we have a team meeting where we bring something interesting to the table.

It could be absolutely anything. It doesn’t have to have anything to do with cancer, it’s just something that we find inspirational. It’s basically again to keep fresh and also to make sure that we’re not just looking at everything within the cancer world.

What other viewpoints have you been taking?

I mean there’s been everything, like ‘how does the UN work the service design for disarmament in certain regions – how has that been brought in?’ There’s been stuff around developing services for big pharmaceuticals around certain types of cancer. There’s some interesting stuff happening in terms of ‘what is service design as an industry, what defines service design?’, so bringing a researcher in to have a debate about that. At what level can you say using service design, is it strategic, is it practical or is it a way of looking at things?

It would be good to hear your thoughts a bit about the rise of AI. More and more traditionally human professions are being disintermediated and people are hypothesising that even professions like law and accountancy are going to get automated. Where do you think service design and the design profession sit within all that?

I’d probably like to answer that by splitting it in two. I think there’s something around service design tapping into the more latent side of what it means to be a human. I mean more hooks into desires and joining things up that doesn’t necessarily always join up. I think it will take a long time before AI is actually going to take anything over because the complexity of delivery, good services and all the different touch points you have just means that a lot of it you will not be able to automate or standardise.

I think you could probably argue that service design will go down a route where it becomes even more specialised around what is a human experience and evolving that. It might be that certain things are taken over by AI but then it’s about how do you join those elements up and make sure you’re not missing something along the way. That’s the answer in terms of the industry. I think, when it comes to service design around healthcare, you have another challenge which is that we’re all humans and we trust other humans.

We would like to make emotional connections, whether that’s with our nurse or somebody at the end of the helpline or a doctor or whatever it might be. There’s something about trusting, firstly. I’m not saying you wouldn’t trust a standardised thing but there’s something about making it a more human experience. I think we are very far from being able to do that with machines, automated things, digital things. I actually think there’s probably a rise in things that are still emotional and tailor made.

Right. Yes, of course.

You might have a really bad day and one service is just not appropriate or one way of communicating with you is just not appropriate. You need to have human intelligence to be able to make that judgement.

Health and sickness is a very interesting field because you have constant moving objectives, constraints, needs, and desires. It’s very difficult to predict. I think it will take a while before a human connection or empathy can be taken over. The way we work the data, the way we demonstrate or exemplify insight work, it could be all sorts of different things but I think there’s an obligation for us as designers to

not just go down one channel in terms of being good verbal storytellers. That’s important but also how you can tell that story has many different layers through using visuals, the way you play with data, use of journey mapping, cartoons, it could be absolutely everything, video, we use it all.

Absolutely. Could you speak a bit about how you’ve set up your team to keep delivering great work?

I am running my team in a very flat way. Everybody except me is called an Innovation Consultant. They’re very deliberately not called service designers because that would put people into a certain group. It’s so open, ‘innovation’ and ‘consultant’. What has been important is to bring a different variety of skills into the teams.

It’s not just design, although that’s really important, but it’s people with a background in sociology or somebody with a background in policy. It’s just very mixed. I think what is important when you’ve built the team, maybe more so when you’ve built it in-house than an agency, is that you have that diversity firstly but that you’re trying to get the right mindset. I care about their attitude and their mindset and how they are in terms of personalities to get them to gel within not just my team but within the organisation.

It’s a little bit different from when you build an agency where you can have more of a distinct identity and you can play around with it a bit. You might, in some periods, go in one direction because UX design is a big thing and you get lots of that. You flex with the market. Whereas I think that when you run an in-house team, your context is that internal environment and you need to make sure that you can create a team that’s good enough.

It’s really important to keep a mix of both being well integrated into the organisation but also understanding when it’s time to just come in and actually do something within your bubble and develop that team.

Any more comments about that mindset and what you mean by that?

What is that mindset? It comes back to a bit of the motto around being firm and flexible. What does that mean? It’s just two words. I think it is that thing about having a pride in your skill set and knowing your skill set relatively well but also understand that in some ways, if you want to land something in a big organisation then you need to mellow and adjust to the context. There are some situations where you have to be a bit hardnosed and say, ‘This is actually what it costs to do good design ethnography’ or, ‘No, sorry, we can’t support on this because it will take up too much time,’ or, ‘You need to commit more time so we can up-skill you.’

Sometimes you have to be addressing what’s needed and other times you just have to be extremely flexible and say, “Okay, that sounds great. Great project, great opportunity. We’ll put more resource into it and we’ll be flexible.” Or we will accept that this is not exactly how we would want to do it in an ideal world. We want to start landing the mindset in the organisation. That means we have to toughen up on what’s good enough or how we might do some things and what is good enough in terms of quality and stuff like that in order to actually up-skill and bring people along with you.

I think that’s maybe where the big difference is between in-house and a consultancy that really feel that we really need to land something in the organisation. Sometimes it’s better to get something implemented that’s better than it would have been without a design focus than sitting and waiting until everything is perfect because that will never necessarily happen. I think there’s something about when do you really push. When is it good enough? When do you actually take people with you on the journey and say, ‘Okay, let’s do it?’

I guess the final question would be when is a service good enough? When is it finished?

It depends how you ask the question. I think it’s good enough when it’s implemented. It’s implemented and it’s delivering to the objectives we set out. I don’t think it always needs to be at the scale but it needs to have landed in one area and we need to have proven that it’s actually serving what it’s set out.

That impact that you mentioned.

Yes

Great. Well you’ve been very helpful, Marianne. Thank you very much.

You’re welcome.

Curious to hear more insights, find your next role, or talk all things innovation? Be sure to message Drew Welton, or register with us to stay in the know!